Graeme Hurry’s Kimota was one of the many small press magazines in which my stories were published, in the days before I was a fat, rich and famous author. The short stories of mine he published are Alternative Hospital, Gurnard, The Torbeast’s Prison, Tiger Tiger and the original booklet of the Mason’s Rats stories. Now he’s publishing Kimota on Kindle – this issue containing Alternative Hospital and stories from other Kimota authors.

Tag: Short Stories

Parasites.

A couple of evenings back I watched an episode of QI, which often comes out with some interesting facts. This particular episode touched on something that’s been a fascination of mine for some years: parasites (and I don’t mean the human kind). Here’s the little darling they were talking about:

The Spotted Rose Snapper Fish, which lives off the coast of California, is oft victim to another freaky parasite. The Cymothoa exigua parasite, a type of crustacean, swims into the fish’s mouth and attaches itself at the base of the poor Snappers tongue. It leeches blood from its victim and as it grows, the tongue withers and dies due to lack of blood supply. Eventually when the tongue dies completely, either diminishing or falling off, the parasite then switches places with the stump and acts as a working replacement for the organ, allowing the fish to use it just like a normal tongue.

The parasite spends the rest of its life living off both the fish’s blood and bits of food that enter the fish’s mouth. The Cymothoa exigua is the only parasite known to effectively replace a body organ.

If any of you have read any of the interviews with me you’ll know that The Skinner and the ensuing Spatterjay books can all be traced back to one instance. I was loaned a book on helminthology (the study of parasitic worms) by a vet, and read through it with growing fascination. I think the thing that got me first was the sheer number of transformations in the lifecycles of various parasites when, before, the limit of my knowledge on such changes was egg-caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly, and how some parasites actually change their host for their own benefit. Two of them stuck in my mind. One includes both ants and sheep in its life cycle. It interferes with the ant’s brain and makes it climb to the top of a stalk of grass and cling there, waiting for a grazing sheep. Another gets inside a snail to breed, but to protect itself, causes the snail to grow a thicker shell. Here, with Cymothoa exigua, are a few more.

This reading resulted in various short stories: The Thrake, The Gurnard, Out of the Leaflight, Choudapt, Spatterjay and Snairls. They then resulted in the novella no one can get hold of: The Parasite. Then I took two short stories, Spatterjay & Snairls, and on the basis of them wrote The Skinner. I definitely must read some more of this stuff.

Wikipedia

It seems I don’t need to write an encyclopedia of the Polity. Here’s the start of a piece on the Prador over at Wikipedia:

Physical description

Prador are amphibious crustaceans with flattened pear-shaped shells with scalloped rims and a raised visual turret at the broad end that houses several pairs of red spider-like eyes, some of which are on movable stalks. Prador move about on six long legs, each terminating in a wicked spike. The rear pair of legs fall off when adolescent Prador make the transition to adults, exposing their sexual organs in the process. Along their underside Prador have four manipulatory arms, each ending in a hand described as “a complex arrangement of hooks and fingers”. These hands are highly dexterous and capable of fine manipulation, just like a human hand. It appears Prador can use all four hands to perform different tasks simultaneously, such as drawing and firing four different weapons at separate targets. Above these are the two heavy “working claws”; large crab-claw limbs that can easily cut through tough materials and crush human bones. Prador feed with a set of dangerous mandibles, capable of grasping, cutting and chewing flesh. Prador are carnivorous, and mostly feed on decaying flesh, primarily harvested from giant mudskippers farmed on their homeworld. Adult Prador are very fond of human flesh, however, and many humans are bred just for this purpose, although by the end of the book The Skinner, this practice has begun to decline. Prador shells are particularly tough, able to withstand impacts and small arms fire, but they seem quite vulnerable to energy weapons and heat, which can cause the shells to burst open.And here’s their entry about me.

Hypochondriac Science Fiction.

Who Killed Science Fiction? won the Hugo Award for Best Fanzine in 1961. The Fifties were rife with talk about the death of science fiction, and Earl Kemp’s symposia of so many sf pros and prominent fans summed it all up.

“When man entered the Space Age two years ago, the writers and editors of science fiction, who had so long been living in this new age, hoped for a fresh surge of reader interest, an expression of gratitude for accurate prophecy in the past and of interest in the possible accuracy of other, as yet unfulfilled prophecies.

“It seemed a logical enough expectation, but it was a fallacious one. The new readers did not arrive—to some extent, at least, because they were put off by the cry of the press (never happier than when it can claim a miracle and coin a cliché): ‘Science has caught up with science fiction!'”

. . . “But facts are impotent against loud and frequent assertion. Readers believe that science has ‘caught up’; and somehow the very fact of s.f.’s accurate prophecies turns into a weapon against it, as if a literature of prophecy should become outmoded the instant one of its predictions was fulfilled.”

Note that in full context, Boucher was not claiming that SF was a literature of prediction, only that sometimes it turned out that way.

The Death of Science Fiction (Again).

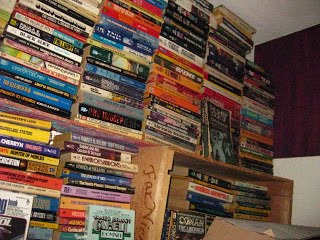

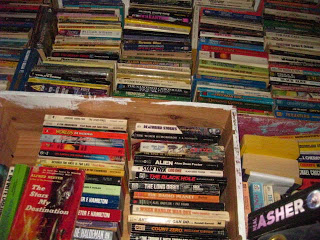

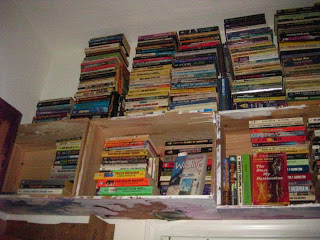

Vaude Part II

Vaude's Collection.

Czech Interview

Here’s an old interview I did for a Czech magazine or website (can’t remember which).

1. You started to write more than 20 years ago, but till 2001 you published only short stories in small press magazines or novellas in rather obscure publishing houses. Since 2001 – and Gridlinked – you have published a new novel every year and now you are in the process of writing the 7th novel. Can you explain the turning point? What has changed more: you and your style or the audience?

I reached my present position by climbing the writing ladder one rung at a time with people stepping on my fingers. I wasn’t published at all for many years, then I had a few short stories published, advanced to novellas and collections and finally to Macmillan. About twenty years ago I completed a fantasy novel and ever after I was sending synopses and sample chapters to large publishers (and writing more books). The turning point was a combination of luck and the skills I’ve learnt. By the time I sent a synopsis to Macmillan there had been a resurgence of interest in science fiction, I had attained a fairly high level of professionalism, and when I sent in my synopsis it was accompanied by excellent reviews of my small press work. The timing was just right, since Peter Lavery at Macmillan was looking for SF & fantasy writers to increase his list. Perhaps a review of The Engineer from the national magazine SFX, which I put on top of they synopsis and sample chapters (of Gridlinked) helped, as did the website I had created which put on display all my other work.

I reckon they continue offering me contracts is because I have learned how to produce and keep on producing, and because my stuff sells. Gridlinked was 65,000 words long when I first submitted it and I extended it to 135,000 in a couple of months (they were worried about this, but upon reading it decided the new version was better than the old); I did the same thing with The Skinner; and all my other books have been submitted early.

Why does my work sell? I suspect the readership has always been there, but that publishers go through fashions. In the 70s and 80s the fashion was for horror, big fantasy, and that the only SF available was dismal dystopian crap. Maybe it’s simply the case that new technologies have brought down the cost of smaller print runs and publishers can now afford to cater for niche markets.

2. You use quite a lot of violence in your books. Or perhaps I should say it better this way: You are able to make up amazing, hard-to-beat- villains and monsters. Where do you find the inspiration for them? Have you read – and enjoyed – Harry Harrison’s Deathworld series?

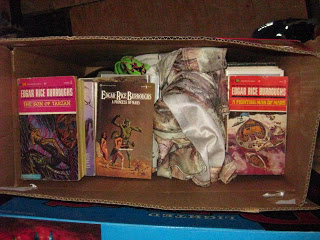

I did read and enjoy Harry Harrison’s Deathworld series (in fact the man himself asked me that), but as I say in the acknowledgements in The Skinner: ‘Thanks to all those excellent people whose names stretch from Aldiss to Zelazny’. In my early teens I started off with Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tolkien, E C Tubb, C S Lewis and have been an SF and fantasy junky ever since, which is not to say that’s all I read. Maybe my characters are inspired by the many thousands of books I’ve read, the films I’ve watched – I could never say for certain. As for my monsters: I’ve always had a great fascination for biology (present and prehistoric) and for monsters in general (I was drawing them as a child at school while everyone else was drawing flowers in plantpots). I always try to make my monsters biologically plausible and create an ecology into which they fit – it’s all part of the enjoyable world-building aspect of SF.

3. Most of your novels take place in one universe, invented by you. The Czech readers have their first chance to disclose this universe in The Skinner, your second novel. What can they expect to find?

To the Line planet Spatterjay come three travellers: Janer brings the eyes of a Hive mind; Erlin comes to find Ambel – the ancient sea captain who can teach her to live; and Sable Keech is a man with a vendetta he will not give up, though he has been dead for seven hundred years.

The world is mostly ocean, where all but a few visitors from the Human Polity remain safely in the island Dome. Outside, the native quasi-immortal hoopers risk the voracious appetite of the planet’s fauna. Somewhere out there is Spatterjay Hoop himself, and monitor Keech will not rest until he can bring this legendary renegade to justice – for hideous crimes commited centuries ago during the Prador Wars.

Keech does not know is that while Hoop’s body roams free on an island wilderness, his living head is confined in a box on board one of the old captain’s ships. Janer, the eternal tourist, is bewildered by this place where sails speak and the people just will not die, but his bewilderment turns to anger when he learns the agenda of the Hive mind. Erlin thinks she has all the time she will ever need to find the answers she requires, and could not be more wrong. And so these three travel and search, not knowing that one of the brutal Prador is about to pay a surreptitious visit, intent on exterminating witnesses to wartime atrocities, nor do they know how terrible is the price of immortality on Spatterjay.

As the fortunes of the recent arrivals unwittingly converge, a major hell is about to erupt in this chaotic waterscape … where minor hell is already a remorseless fact of everyday life – and death.

4. Your books from the Polity universe have two main characters, a monitor Sable Keech and an agent Ian Cormac. They are both the good guys, fighting for ESC. Is it possible for them to meet in some of your works? And on the same side?

I’ve recently been working out the chronology of my books and what you say is entirely possible. Sable Keech is killed then reified about seventy-five years before the events of Gridlinked. The events of The Skinner then take place seven hundred years after his death. This basically means that Keech, reified (a high-tech zombie), is about in the Polity universe while the events in Gridlinked and subsequent Cormac books take place. Also, if Cormac survives his present trials, he may meet up with Keech some time in the future. Remember, these people do not die of old age!

5. You are considered to be one of the writers of so called New Space Opera, which – in my opinion – succeeded in giving a new push, new blood, to the SF genre, at least in the 1st decade of the new millenium. Can you compare the original space opera and the new one?

Nothing gets out of date quite so fast as science fiction, simply because it has to keep up with, and look ahead of, current science and technology (how many of those old writers predicted the personal computer, the Internet?). I read stuff like E E Doc Smith’s Skylark of Space series and enjoyed it thoroughly at the time, but now, picking up books like that and reading about an astrogator working something out on a slide rule just kills that ‘suspension of disbelief’ on which all space opera (and all SF) depends. I also think many of the older space operas were written in a time of greater naivety too. The characters and storylines now possess a harder edge; a greater understanding on the part of the author of how human beings, political systems, ecologies and much else actually operate. I now only read the old stuff out of nostalgia, and admiration of the story-telling skills of the writer concerned.

6. One of the most influential NSO writers seems to be Alastair Reynolds, whose novels started to be published one year sooner than yours. You use some similar methods and properties, such as “melding plague” and “nanomycelium”. Has it ever happen that some reviever used these similarities against you?

I briefly talked to Alastair Reynolds about this. I’d written my first three books before I even picked up one of his (which I thoroughly enjoyed). I think it comes down to the fact that some ideas have their time. All SF is built upon what went before and what is currently being explored by scientists. Ideas concerning nanotechnology have been knocking around for decades and many SF writers are picking them up and using them. It is unsurprising that, as a result, those writers will come up with scenarios similar to each other’s. Though I think I’m right in saying that, because of my biological interests (specifically in fungi) I was probably the first to come up with nanomycelia. No reviewers have yet accused me of plagiarism. I’m not too bothered if they do because I can always prove them wrong. Jain technology, for example, appeared in my short story collection The Engineer in 1998, and my first nanomycelium story appeared in a magazine called Premonitions in 1992.

7. In the Line of Polity, your third novel, the force of evil is theocracy. Other than that, you do not use religion in your books too much. Was there some other reason for it except the one that you just needed some bad guys?

I take the view that as individual knowledge and access to information increases, primitive belief systems will continue to collapse. I don’t see how our beliefs in parochial gods will survive us encountering, in the future, the vastness of space and the further revelations of science. The Theocracy was a one-off created by special circumstances. And yes: I needed some bad guys.

8. On your webpage you posted samples of your fantasy novels – unpublished yet – that you wrote some years ago. Have you some plans with them? Do you think they may be interesting for the Czech readers?

One day I intend to rewrite those fantasy novels and offer them for publication, but at present I’m heavily involved in the Polity universe and will keep on writing novels set in it while Macmillan continues offering me contracts. I like to think the fantasy novels would be of interest to many readers and did want to give myself a breathing space so I could turn my attention to them, to a contemporary novel I wrote some time ago, to my TV scripts, but that seems increasingly unlikely. One book a year for Macmillan may soon be changing to one book every nine months, I’ve got short stories and novellas I need to write because I already have a market for them … so much to do and so little time.

Interviews

Here’s an interview with me over at The Book Depository.

Here’s another one over at Next Read.

There was another one I did recently but I can’t find it. These things tend to get a little samey anyway.

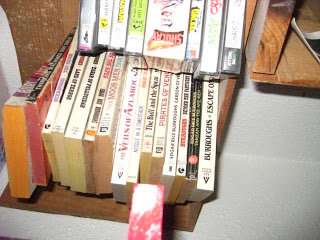

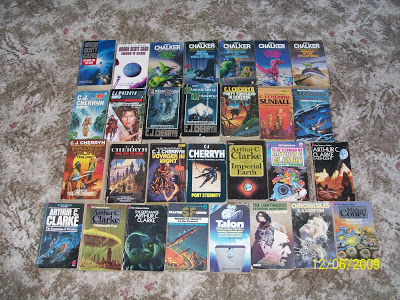

C is Cherryh and Clarke

And another one with a books missing. Where the hell is my copy of Wyrms by Orson Scott Card? I think that’s probably the best book of his I’ve read.

| ORSON SCOTT CARD | ENDER’S GAME – SPEAKER FOR THE DEAD . |

| JACK L CHALKER | EXILES AT THE WELL OF SOULS QUEST FOR THE WELL OF SOULS THE RETURN OF NATHAN BRAZIL TWILIGHT AT THE WELL OF SOULS MIDNIGHT AT THE WELL OF SOULS |

| C J CHERRYH | HESTIA EXILE’S GATE THE CHRONICLES OF MORGAINE SUNFALL FORTY THOUSAND AT GEHENNA MERCHANTER’S LUCK ANGEL WITH SWORD THE FADED SUN (TRILOGY) VOYAGER IN NIGHT PORT ETERNITY THE PALADIN |

| ARTHUR C CLARKE | IMPERIAL EARTH REACH FOR TOMORROW EARTHLIGHT THE FOUNTAINS OF PARADISE CHILDHOOD’S END THE DEEP RANGE |

| HAL CLEMENT | MISSION OF GRAVITY |

| JAMES COULTRANE | TALON |

| D G COMPTON | THE CONTINUOUS KATHERINE MORTENHOE CHRONICULES |

| MICHAEL CONEY | BRONTOMEK |